from the Greek karabos or Arabic qârib

Replica Boa Esperança

the present day direct descendant

Print this page | Age of Discovery | World Map | Battle of Diu | Forefather of the Beaufort Table | Naval administration | Longitude | XVIcentury Ships

Discovery of Australia

According to

Portuguese Naval records, Australia was discovered by

Cristovão de Mendonça in 1522, and Gomes de Sequeira in 1525.

See Map at National

Gallery in Australia

More Australian

Coast Maps of the 1500s, the Dieppe Maps

Book "Beyond

Capricorn", by Peter Trickett.

| Then

and now |

||

|

|

|

| CARAVEL from the Greek karabos or Arabic qârib Replica Boa Esperança |

Sagres

II the present day direct descendant |

|

There had been previous visits

by Arab and SE Asian sailors.

By the end of the XV century the Ottoman Empire - the "Moors" - still

terrorized Europe,

and had control over the Indian Ocean.

|

The Muslims were no friends of the Portuguese seaborne crusaders - not after the Moor invasion and occupation of Portugal, that had taken more than a century to repell. A Chronicle

of the Battle of Diu By

Rui Soares, one of the Portuguese Ship's Captains at the battle. Circa 1503: Portugal establishes feitorias (a trade/military fortress defending a safe harbour) for its fleets on the East African coast, on the route for its new fortified warehouses in India. There, the Muslims were no friends of the Hindus. In Goa, the Hindus were forced to submit to Islam or face death. To oppose the Portuguese expansion in the East, Mahmud Begara, sovereign of Guzerate, in India, enters into an alliance with the Sultan of Egypt and in early 1507 an Egyptian squadron is sent to India. March 1508: The egypto-guzerate forces surprise in Chaúl (Dabul) a small Portuguese fleet. After three days of combat two Portuguese ships manage to escape, while the remainder are taken, with casualties and hundreds of prisioners. Among the casualties is D. Lourenço, son of the Portuguese viceroy, D. Francisco de Almeida. The news of the death of D. Lourenço in the battle of Chaul enrages D. Francisco de Almeida as if lightning had struck at his feet. For some days he locked himself in his chambers, refusing to see or speak to anyone. Later, he returned to his normal life, as if nothing had happened. But, from behind his impassive countenance, one perceived that he burnt like a volcano about to blow, the desire for revenge. "He who ate the chick has to eat the rooster, or pay for it", he said. However, that year nothing could be done, with the "monsoon" about to arrive. During the wet season, he used the time to advantage, by successively careening all the ships that were in Cochim and fitting them, with sight to the operations planned for the end of the year. When the "good weather" returned, the first thing the viceroi did was to order Pêro Barreto with a fleet of three naus, six caravels and two gales to block Calicut, as he had been informed that the Samorim, the city's ruler, was organizing an army to join the ones of Mir-Hocem, Commander of the egypto-guzerate squadron, and Meliqueaz, Captain of Diu. The truth is that when Pêro Barreto arrived in Calicut, the paraus of the Samorim had already gone the way of Diu. In the Autumn of 1508, thanks to a happy coincidence, two fleets from the Kingdom arrived in India: the one from that year and the one from the previous year, that had wintered in Mozambique. Therefore, he had no lack of men, weapons and all other equipment necessary to equip the ships conveniently to go fight the moors. But, before thinking of war was necessary to deal with business. Up to the 20th of November, D. Francisco de Almeida was held in Cochim, overseeing the loading of the return-trip naus. On this date he left for Cananor with nine naus, two of which were cargo vessels, and one bergantim. Having dispatched the two cargo ships for Lisbon, the viceroi was preparing himself to join Pêro Barreto when what he feared most happened: on the 6th of December, Alfonso de Albuquerque arrived from Cananor and required him to deliver the government of India! D. Francisco de Almeida was in a dramatic situation of conflict. He knew he had no valid reason to disobey the King’s orders, but was not resigned to leave India without having avenged the death of his son by his own hands. Finally, the paternal feeling prevailed over discipline. Invoking futile reasons, adamantly refused to hand over the government before giving combat to the Turk (egypto-guzerate) raiders, now joined by local Muslim forces. In consequence, Alfonso de Albuquerque followed for Cochim and D. Francisco de Almeida, on the 12 of December, departed for Calicut.

Joining his fleet with the one of Pêro Barreto and besides a small nau and three caravelas that had to stay in the blockade of Calicut, The viceroi found himself with the following ships: five great naus, the “Flower of the Sea”, skippered by João da Nova, where the viceroi himself was embarked, the “Belém”, of Jorge de Melo Pereira, the “Espírito Santo”, of Nuno Vaz Pereira, the “Great Taforea” , of Pêro Barreto de Magalhães, and the “Great King” , of Francisco de Távora; four small naus, the “Small Taforea”, of Garcia de Sousa, the “Saint António” , of Martim Coelho, the ”Small King” , of Manuel Teles Barreto, and the “Andorinho” , of D. António de Noronha; four caravelas rodondas, skippered, respectively, by António do Campo, Pêro Cão, Filipe Rodrigues and Rui Soares; two caravelas latinas of Alvaro Paçanha and Luís Preto; the galés of Paio Rodrigues de Sousa and Diogo Pires de Miranda; bergantim of Simão Martins. In total, eighteen vessels provided with about a thousand and five hundred Portuguese and four hundred Malabar’s from Cochim and Cananor.

In those days it was a captains' custom to, before launching into an operation of responsibility, undertake an easier one with the triple objective to train their men, fortify their moral and, if possible, frighten the enemy. Still in Cananor, the matter is discussed between D. Francisco de Almeida and the captains. The plan to attack Calicut was set aside for being too risky. In its place, it was determined to attack Baticala, whose king was at war with Timoja, our vassal. But, upon arrival in the city, they found out that peace had already been settled. After having touched in Onor to embark provisions supplied by Timoja, that had his base there, the Portuguese fleet headed for the island of Angediva, in order to resupply with water. On this island, D. Francisco de Almeida used the chance to advantage and again congregated the advice of the captains, during which was discussed the plan to adopt in the event of meeting the Rumes at sea. In accordance with this plan, the "Flor do Mar", with the viceroi aboard, would approach the vessel of Mir-Hocem. It was also decided that if, however, the fleet of Rumes were not found, the Portuguese would attack Dabul. From Angediva, the trip turned very slow because the dominant winds were from the northern quadrants. On the 29th of December they sighted Dabul and, the following day, the fleet crossed the bar and immediately anchored next to the city, beginning the landing. The fight was terrible, because the city, in contrast of what was assumed, was provided with more than six thousand resolute men, solidly entrenched in bastions well furnished with artillery. Moreover, there was in the port four great naus of Cambaia that also fought bravely. Nonetheless, the city and the vessels were taken, the enemy having lost in the battle over a thousand five hundred men. The Portuguese, lost sixteen men and had two hundred and twenty wounded. D. Francisco de Almeida spent the night ashore and, the following day, authorized the looting. But, soon afterwards it started, seeing that the soldiers dangerously dispersed in the neighborhood of an enemy who still had many forces, ordered the city to be burnt and re-embarked. Still in Dabul D. Francisco received two letters. One from Meliqueaz proposing peace and friendship and another from the captives of Chaul, that he had in its power, saying that they were being treated very well . Such manifestations of fear on the part of the enemy, strait after the victory in Dabul, had considerably fortified the moral of the Portuguese. On the 5 of January, the fleet continued on its trip north. Passing Chaul demanded payment of taxes from the captain of the Nizamaluco, lord of the city. But he did not, at that moment, have the money necessary, being agreed that he would pay when the viceroi returned from Diu. From Chaul, the fleet headed for Maim, on the island of Salcete, next to Bombay. Preoccupied with the lack of provisions, the galés, along the way, went assaulting the coastal villages with to get them. In one of these assaults, Paio de Sousa, captain of one of them, fell in an ambush and died there. His galley was given to Diogo Pires and his passed to a noble called Diogo Mendes. Days later this galley was in danger of being lost. Having boarded carelessly one fusta of Diu that seemed weakly provided, Diogo Mendes was suddenly confronted with a large group of well armed and resolute Turks, who had hidden on their approach, and that now invaded his ship and determined to take her. In the end, the Portuguese managed to recover and all the assailants were killed. In the fusta did not find provisions nor anything of value, besides a Hungarian young woman of rare beauty that Diogo Mendes took to the nau of the viceroi and that, later, would come to marry a Portuguese noble in Cochim. In Maim, finally obtained, by purchase, the provisions that our fleet so desperately needed. From there D. Francisco de Almeida sent a letter to Meliqueaz, that said thus:

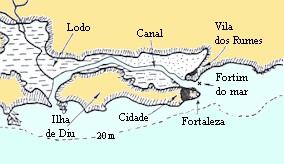

But the passage from Maim to Diu revealed more difficult than it seemed, due to contrary winds. Not managing to make way along the coast, the pilots advised D. Francisco de Almeida to go out to sea. However, after a few days, and finding themselves completely lost, the pilots declared that, already was not possible to reach Diu before the "monsoon", and to consider returning to Cochim. As one can imagine, D. Francisco despaired and had brought to his presence the pilots of some "naus of Mecca" that had been captured during the trip. One of them soon declared he would take the fleet to Diu if his freedom was granted. The Vice-Rei readily accepted and, in accordance with his advice and despite the skepticism of the Portuguese pilots, ordered the course changed to Southeast. On the dawn of 2nd day of February, Diu, in all its opulence, was in sight!  Island of Diu Let us now see what happens, however, in the enemy field. After the battle of Chaul, celebrated by the "moors" as having been a great victory, Mir-Hocem and Meliqueaz had become heroes in the eyes of all the Muslim of India. However, in their soul, neither of them shared the euphoria of their coreligionists. Soon after the battle Meliqueaz had sent a letter to D. Francisco de Almeida bragging the courage of his son and friends and guaranteeing that the Portuguese prisoners, whom he had in his power, would be well treated, as they had really been. However, calculating correctly that this would not be sufficient to calm the anger of viceroi, he took care to strengthen the fleet by providing four well provided naus furnished with artillery, one of which of great size, and orders to construct and equip more fustas. In turn, Mir-Hocem, feeling equally insecure, does not spare efforts to repair his fleet from the damage suffered in Chaul. However, and despite the financial aid received from the "moors" of Diu, his situation was not brilliant. It is certain that he saw his fleet increase with the arrival of the galeon that was left behind when he left the Red Sea; but he lacked people; from one thousand five hundred men with whom he left Suez, two years before, only remained little more than eight hundred. To further increase the concerns of Meliqueaz and Mir-Hocem, from October it started to transpire in Diu that, after the "monsoon", in Cochim arrived numerous naus from Portugal, with many people of arms, which was the truth. From there both agreed to adopt the strategy to conserve the armies in Diu, leaving the initiative to the Portuguese. With the conquest of Dabul and the arrival of the letter of D. Francisco de Almeida all doubts faded, if they still had any. Meliqueaz and Mir-Hocem understood that they did not have a way to prevent a battle without quarter with the viceroi. The first cursed the hour when the Turks had decided to choose Diu for base of operations; the second, feeling that his partner would not hesitate in delivering him to save the city, only thought of finding a dandy way of being able to escape for the Red sea. The truth is that D. Francisco de Almeida had lead the psychological war as a true master and, through it, already had half the battle won before arriving at Diu. As soon as it transpired that the Portuguese fleet was nearby, Meliqueaz and Mir-Hocem had a meeting to decide what tactic to adopt. The Turk was of the opinion that they had to fight the Portuguese at sea to take advantage of the enormous numerical superiority that they had in rowing-ships: six Turkish gales and galeotas, about fifty fustas of Diu and as many paraus of Calicut, all very furnished with artillery and well provided with war hardened people. But Meliqueaz was categorically opposed , for he knew well that if things started to run badly, which seemed to be the most likely outcome, Mir-Hocem would not hesitate in beating in withdrawal for the Red sea, leaving him alone to account with the viceroi. Therefore, he insisted that they fought anchored, in order to benefit from the support of the artillery from the fort and the seaward fortress as well as what they had ordered to be placed on land, giving clear understanding to Mir-Hocem that if he left for sea neither his fustas nor the paraus from Calicut would follow him. But the astuteness of Meliqueaz did not stop there. With the excuse of his presence being indispensable in a war he was involved in the continent, he abandoned Diu, leaving to Mir-Hocem the prickly task of, alone, make the honors of the house to the viceroi! However, he was not a man to be outmaneuvered easily, as will be seen ahead. On the 2nd day of February, in the afternoon, when the Portuguese fleet anchored to the east of Diu, Mir-Hocem ordered an attack by the rowing ships, which resulted in a duel of artillery without consequence, given that the engagement was at great distance and the swell made it difficult to aim. After some time, the enemy ships ceased their attacks and went to anchor close to the coast, in the shallows that separate the outer harbour from the inner harbour. Shortly afterwards, they were joined by the four naus of Diu, by order of Mir-Hocem. Would he have had in mind to sacrifice Meliqueaz’s fleet to break the impetus of the Portuguese, before entering action with his own ships, or would he be thinking about, in the following morning, to also come with these out of the shallows? We will never know! Although absent from the city, Meliqueaz was kept up to date by couriers. As soon as he knew Mir-Hocem had ordered his fleet out of the shallows, he returned at a gallop and commanded that his naus and fustas, as well as paraus of Calicut, return to the inside. , The plans that Meliqueaz and Mir-Hocem had been deceiving each other, with failed in this way. The first was forced to remain in Diu during the battle; the second, was stopped from using the fleet of the other as a scapegoat.

That night, D. Francisco de Almeida congregated, for the last time, the advice of the captains to seat in the tactical plan to use the following day. Right from the start, the captains, unanimously, had asked for D. Francisco to give up the idea of being the first one to approach the vessel of Mir-Hocem, insisting that he remained in a position moved away from the combat in order to be able to direct the battle in its set. D. Francisco de Almeida acceded, being determined that the “"Flor de Mar"” would not board any of the enemy and would be limited, with cannon fire, to hinder the enemy rowing-ships that bothered the Portuguese vessels in charge of the boarding. It will be opportune to relate that the problem of the position the commander in chief of a fleet has to occupy during battle always worried naval war theoreticians. In most recent times, the predominant thesis was the one that should have remained, out of the line of battle and wind[fire]ward (sotafogo) of it. Therefore, this was, necessarily, the solution adopted by the Portuguese in the battle of Diu which gave such good results. In the council referred to above was also made what today we would call the distribution targets: the four great naus (besides the "Flor do Mar") would approach the four Turkish naus; the four small naus would approach the four naus of Diu; two caravelas redondas would approach the two Turkish caravelas; the others two would approach where it seemed to them more convenient; one of the gales would go in front of the naus sounding the channel; the another one, possibly, would have had order to remain in the immediacy of this, in order to help any ship that by misadventure ran aground; the two caravelas latinas would assist the “"Flor de Mar"” in its task to bar the passage to the enemy rowing-ships; the bergantim would remain in the neighborhood to transmit the orders of viceroi. In spite of all, the problem that at that moment seemed most difficult to decide was of the crossing of the exterior port to the inner harbour through the narrow channel that connects them. Happily, among the captives that our fleet carried was a youngster of eighteen years who had already a few times to Diu and that taught the deep water of the entrance to the Portuguese pilots. Finished the meeting and in consequence of the decisions made, most of the nobles and soldiers of the “"Flor de Mar" “ were distributed among the other vessels, mostly for the ones that had to go in the vanguard. Until high hours of the night the sailors and the carpenters had been strengthening the edges of the ships with gunwales and covering them with strong nets of cairo, of pressed mesh, while the soldiers prepared the weapons and they confessed and they sought absolution. Later, silence came and each one was alone with the anguish that precedes the day of battle. On the deck of the ships, the guards, looking intent, looked for any indication of approach from the enemy. But, in that night, nothing more happened. At dawn on the 3rd of February, verifying that all the enemy ships continued put inside of the port, D. Francisco de Almeida ordered to deliver to each one of the captains this message:

By nine in the morning a gentle northeast started to blow , which was the most convenient wind for the Portuguese fleet. But D. Francisco de Almeida still had to wait for the tide. Forced to pass his fleet through a relatively narrow canal (150 m) and shallow (5 m), would not attempt it, certainly, without being with the incoming tide, to have the possibility to free any ship that might run aground. Meanwhile, he ordered

the bergantim to again distribute among the ships the proclamation of

the rewards that would be allocated, in case victory smiled on the Portuguese,

as he hoped. This proclamation consisted, beyond the prizes attributed

to the captains, soldiers, sailors, bombardiers, etc., of the indemnity

to be granted to the wounded and the families of the deceased and the

promise of freedom to the slaves. Finally, about eleven o’clock, having come together the ideal conditions of wind and tide, and having his people strongly motivated and anxious for action, D. Francisco de Almeida ordered a bombard to go off, which was the combined signal to initiate the attack. In all the ships, the trumpets and the drums filled the air with their martial tunes, at the same time that the garrisons came alive and made great commotion. On the enemy side, the naus and the rowing-ships had answered immediately in the same way. The great moment had arrived! The Portuguese naus, already short scoped , aweighed anchors, released jibs and mizzens, and headed, in the order, for the entrance of the channel, preceded by the gale of Diogo Pires that continuously sounded. The first nau to enter was the “Espírito Santo”, of Nuno Vaz Pereira, an old vessel, that leaked like a sieve and, therefore, was placed at the front, assuming that it could be lost, since the first ship to enter would be the one running the greatest risks. Effectively, as soon as the “Espírito Santo" and the gale of Diogo Pires entered the channel to the inner harbour they started to be shelled by the fortress, by the seaward fort and by the rowing-ships of the enemy, suffering heavy damage from all. Both the Turkish naus and the ones of Diu were heavily armored and with the castles and decks covered with strong nets of cairo. Moreover, they had the topsides protected by fenders consisting by bags of cotton covered with wet ox skins, because of fires. Moments before approaching the vessel of Mir-Hocem, the "Espírito Santo" let off all its portside cannons against the hull of the Turkish nau that was rafted to her starboard. The effect of this salvo, gone off at the shortest distance with cannons of thick bore, was devastating, opening a gap in the water line, through which water started to enter in great amounts, making the nau list dangerously. Trying to counterbalance the list, all its garrison transferred to the other edge. It is certain that the vessel straightened, but the water that had embarked also ran to this side and caused her to capsize, to the acclamations of the garrison of the "Espírito Santo"! Everything happened so quickly that few were the Turks that managed to save themselves from drowning. However, immediately after firing its artillery, the “Espírito Santo", with a greater draught than the Turkish naus, touched the bottom and was immobilized a few meters away from the nau of Mir-Hocem. Thinking that the Portuguese had purposefully grounded in that position to send their nau to the bottom with their artillery as they had done with the other, they hauled on the port iron's cable and grappled the nau of Nuno Vaz that, by the way, did not desire another thing. As soon as the two naus joined, the Portuguese jumped impetuously on the enemy ship and in a few minutes they had taken the forecastle and the deck. However, at the moment where it seemed that the Turkish flagship was irretrievably lost, one of the galleons, that was to port, shortened on the starboard anchor and boarded the "Espírito Santo" on the opposite side to the one grappled to the vessel of Mir-Hocem. In this way, it was our vessel stuck between two Turkish ships, seeing itself obliged to fight simultaneously with both. In result of this, part of the knights and soldiers who were in the vessel of Mir-Hocem had to return hastily to their vessel to defend from the attack of the galleon. During this, Nuno Vaz Pereira was seriously wounded by an arrow that crossed his throat and had to be evacuated in arms. From this moment, the garrison of the “Espírito Santo” was forced to adopt a defensive attitude, limited to repel the successive assaults of the Turks for both sides. The second vessel to enter should have been the "Belém", of Jorge de Melo Pereira. But it took too long to hoist the anchor. Pêro Barreto, in the “Great Taforea”, passed in front and crossed the channel without incident, headed for the Turkish nau that was her target, the third, which grappled to starboard. But, as this also had one other moored to itself, Pêro Barreto and his friends had to deal with, at the same time, the garrisons of two vessels, which made for a drawn out combat. Meanwhile, Jorge de Melo was furious for having been overtaken and couldn’t get enough of insulting the master! And, to try to recoup the delay, as soon as the iron pulled out, ordered the mainsail hoisted , besides the jib and the mizzen. The result was that the vessel gained speed and, before the sails could again be lowered, went past all the Turkish vessels and even the great nau of Diu, finishing up only managing to board, on starboard, the group of two naus of this city that were next! In this way was lost for combat with the Turks the best and most provided nau of our fleet. The fourth nau to enter was the Great King, of Francisco de Távora. In its wake went the "Frol of la Mar", of João da Nova, with the Vice-Rei. Seeing what happened with the "Belém" and realizing that the "Espírito Santo" was in difficulties, it is probable that he ordered Francisco de Távora, that preceded him, and Garcia de Sousa, that followed him, to board the vessel of Mir-Hocem, which they did. The arrival of the "Great Taforea" with fresh people made the combat in the Turkish flagship definitively hang in our favor. Although they continued to offer a desperate resistance, its occupants had been obliged to abandon the exterior and to take refuge below decks, where they all ended up being killed or made prisoner. Mir-Hocem, already wounded and seeing the nau lost, was transferred to a small boat that was moored by the poop and, using to advantage the confusion of the battle, crossed the channel without being noticed and escaped to the village of Rumes. There, he mounted a horse and ran away at a gallop for Cambaia, with more distrust of Meliqueaz than of the Portuguese. However, the "Small Taforea", of Garcia de Sousa, had also rafted alongside the Turkish flagship, helping to dominate the last spots of resistance. The "Flor de Mar", when she reached the interior harbour, covered the short distance close to the battle line so that the Vice-Rei could appraise the situation. Passing the last Turkish nau, when starting to turn to starboard, her port artillery fired. Once again the effect of a salvo of thick bore at close-range was devastating. The Turkish nau suffered a gap in the starboard bow, close to the water line, and started to sink. However, it is natural that most of its garrison was saved, either by fighting against Pêro Barreto in the neighbouring nau or by having time to get across before the nau sunk. At this point we cannot avoid thinking that the sinking of two Turkish naus, each one with a single salvo of artillery, came to give weight to reports by an officer (condestavel) in the nau of D. Lourenço de Almeida who, in the battle of Chaul, had said that was possible to sink the Turkish fleet by cannon. Either way, it seems certain that the Portuguese had learned the lesson. In Diu, all our naus that had been able to do it, before approaching the enemy, would let off, at pointblank, all its artillery. Continuing underway, “Flor do Mar” went to anchor sensibly in front of the naus of Diu, in the middle of the channel, in order to bar the passage of the rowing-ships, that did not cease to afflict, with canons(pelouros) and arrows, the vessels as they entered, although with poor results. The truth is that Meliqueaz’s decision to give battle in the interior harbour instead of the outer one or at sea was extremely favorable for the Portuguese, inasmuch as the main force of the enemy, with its smashing superiority in rowing-ships, was practically annulled. In a channel barely two hundred meters wide, was only possible to the gales, galeotas, fustas or paraus to fight in a front of, at the most, twelve vessels, which, even then, had to be very close, which enormously facilitated the job of our artillery. On the other hand, the great amount of boats that they had behind them hindered the maneuvering of the ones that were more directly engaged in combat. From the moment that the Portuguese naus started to arrive in the interior harbour, continuously letting off the starboard batteries, the enemy rowing-ships begun to suffer much damage and casualties and to be pushed inside. After the "Flor de Mar" anchored, the attacks of the rowing-ships had been practically concentrated on it, leaving all the other vessels from being bothered. Half blind and suffocated by smoke, the artillery of our flagship had their hands full, salvo after salvo on the gale, galeotas, fustas and paraus, of which more then a dozen had sunk and many more were seriously damaged. After the battle it was calculated that, in that afternoon, the guns of the "Flor de Mar" would have fired more then a thousand nine hundred cannonballs! For its part, the vessels and rowing-ships of the enemy were not behind. In some of the Portuguese ships they had been able to count, after the battle, more than five thousand arrows and hundreds of cannonballs! Meanwhile, the "Santo António", of Martim Coelho arrived. Once Garcias de Sousa was deviated for the attack to the vessel of Mir-Hocem, he had the hardest bone to chew: the attack on the great nau of Diu. The difficulty in approaching this vessel was that, besides being very high-sided, she was completely enclosed with a kind of wooden roof, only being able to be entered by the artillery doors. But this was not easy, not only because of the firing of the cannons but also because of the seven hundred men who provided it. Most were skillful archers that continuously fired clouds of arrows on the assailants. No matter how hard they tried, the Portuguese had not managed to enter her. After the “Santo Antonio” of Manuel Teles Barreto it is possible that the “Small King” entered the harbour, who, logically, must have approached the third nau of Diu, where, for certain, they did not find any great resistance since most of the garrison of this nau had to be in the neighbouring nau to fight the people of Jorge de Melo Pereira. The last nau to enter would have probably been the “Andorinho”, of D.António de Noronha, that, obviously, would have gone for the last nau of Diu. Coming close to her by starboard, it is likely that, moments before the boarding, they also let off a volley of artillery at point blank, of that it came to result, shortly afterwards, its sinking, not being possible to know if the boarding did indeed take place, although it seems most likely that it did. After the naus, entered the caravelas redondas. The first was António de Campo’s, headed for the Turkish galleon that had boarded the nau of Nuno Vaz Pereira on his starboard. Grappled and took it without difficulty, given that most of its garrison had already been deceased or taken prisoner in the vessel of Mir-Hocem. The same did not happen with Pêro Cão’s caravela, that entered next. Having boarded the second Turkish galleon that was intact, they found serious difficulties. To complicate matters, the caravela, that had been poorly grappled, was freed and sent adrift, only with grooms (grumetes) and pages on board, leaving Pêro Cão and his friends, who were little more than twenty, isolated on the enemy ship, to give accounts to close to a hundred Turks. Shortly afterwards, Pêro Cão was killed, making the situation even more critical. It is natural that António de Campo, that was to the side, would have realized the difficulties the people on the other caravela found themselves in and, releasing the galleon that they had taken, readily went to their aid. After a hard fight, the Turkish galleon was also taken, while the first one, abandoned, went adrift to run aground on the beach. The third caravela to enter was of Filipe de Rodrigues. By now all the Turkish naus of Diu were dominated, as well as the two galleons, to the exception of the great nau of Diu. Therefore, it is natural that he approached, from the opposite side to where the “Santo António” was grappled. Finally the caravela of the narrator, Rui Soares, entered, followed, probably, by the two caravelas latinas and the gallena of Diogo Mendes. As soon as they entered, they realized that the battle was irretrievably lost. The paraus of Calicut had set in escape, leaving for sea through the other entrance of the channel that skirts the island of Diu. In turn, the Turkish gales and galeotas, as well as fustas of Meliqueaz, had also started to withdraw. Not having any nau or galleon to approach, Rui Soares, the narrator, set upon the rowing-ships as they beat in withdrawal and, putting himself self in between two Turkish gales, grappled them both and took them by assault, which earned him great praise from the viceroi. By this time our sailors and soldiers were already in the dories killing the Turks and the "moors" that tried to swim for the shore. But still, the great nau of Diu continued to resist. Seeing this, D. Francisco de Almeida ordered Garcia de Sousa, who was the one with most rested people, to go give aid to Martim Coelho and Filipe Rodrigues. But, in spite of all the attempts made by the three ships, it was not possible to penetrate the nau. Then, Garcia de Sousa ordered to move the ships away and gave order to sink the nau with artillery. Under continuous canon fire, the gunwales crumbled, the topsides opened gaps and the nau started to sink slowly. It only remained, for the tenders, to exterminate the occupants who jumped in the water. The battle finishes with a thundering Portuguese victory! Without having lost a single ship, captured two Turkish naus and two from Diu. Two Turkish naus and two galleons had sunk, as well as two naus from Diu, besides having sunk several fustas and paraus, seriously damaged many more and captured two Turkish gales. Of the Portuguese, thirty two had died, among them the captains of two ships (Nuno Vaz Pereira and Pêro Cão) and more than three hundred were wounded. Of the eight hundred men who provided the Turkish fleet only twenty two managed to swim ashore. All the others had been killed or made prisoner. All together, the enemy had over three thousand dead and a even larger number of wounded. By five in the afternoon, the wind had shifted, probably, to the north or the northwest and with the tide beginning to ebb, D. Francisco de Almeida decided to take the fleet to the exterior harbour, taking care of the fact that the land artillery continued to afflict his ships and that, on the other hand, he feared an attack during the night by fustas or fire ships. Although carried out already during twilight, the exit was done without incident. In the inner harbour, they only left behind the gales and some naus to hinder the "moors" from taking things from the naus that had been captured. Once the fleet was safely anchored in the outer harbour, the garrisons of the ships noisily celebrated the victory until high hours of the night, while D. Francisco de Almeida congratulated them, one by one, hugging the nobles and the soldiers and comforting the wounded. The next morning, still before sunrise, one fusta with a truce flag approached the fleet bringing the unconditional surrender of Meliqueaz and with it the delivery of the city of Diu. Having received the message, D.Francisco de Almeida demanded, as a prerequisite to any negotiation, the immediate delivery of the prisoners of Chaul. One hour later, the prisoners arrived aboard, to the sound of trumpets and drums, and, with tears of joy running down their faces, fell in the arms of their friends. They wore silk dresses and each one of them brought fifty gold xerafins that Meliqueaz ordered be given to them! The signing of a peace treaty (that was written on a gold leaf) did not pose any difficulty. D. Francisco de Almeida declined the offer of the city of Diu since, in his understanding, would be very expensive to keep, limiting it to leave one garrison (feitoria). He demanded the delivery of the four galeotas of Mir-Hocem, the Turks who had managed to run away for land and the artillery of the sunken vessels, besides an indemnity of three hundred thousand gold xerafins paid by the "moor" traders that financed the refitting of the fleet of Rumes, from which one hundred thousand were distributed among the garrisons of our ships. Meliqueaz accepted everything, managing, however, to replace the delivery of the Turks by their expulsion from his dominion. Having managed to prevent what he feared the most, the looting and burning of the city, be gladly accumulated the Portuguese with gentility. Rare was the day when he did not send to our fleet one fusta loaded with sheep, hens, eggs, oranges, lemons, cabbages, etc. To the nobles, he offered rich gifts. But D. Francisco de Almeida did not accept anything for himself, not even a string of pearls and a tapestry (brocade) that Meliqueaz gave him for his daughter, and that he sent to the Queen. In exchange for the favors of Meliqueaz, the two naus that had been taken in the battle were returned to him. The Turkish galleons were probably sold, and the proceeds distributed among the garrisons of our ships. The two naus remained in Diu to load provisions destined for Cochim. Four galeotas were burnt. The two gales captured by the narrator Rui Soares were naturally taken to Cochim as trophies. The spoils of the battle included three royal flags from the sultan of Cairo, that were sent to Portugal and are still today displayed in the convent of Christ, in the town of Tomar. Regarding the Turkish captives, D. Francisco de Almeida was inclement, ordering most of them to be hang, burn alive or to be torn to pieces by tying them to the mouths of the cannons. Having avenged the death of his son, settled affairs in Diu, and arranged for the dispatch of two vessels with provisions for Socotorá, D. Francisco de Almeida, on the 12th of February, began with the remainder of the fleet the triumphal return to Cochim. The battle of Diu,

although overshadowed by the cruel treatment D. Francisco de Almeida inflicted

on the Turkish prisoners, is, undoubtedly, the most important of all Portuguese

Naval History and one of most important of World Naval History.

From a tactical point of view, it was a battle of annihilation that finds parallel only in Lepanto (1571), Aboukir (Nile-1798), Trafalgar (1805) or Tsuchima (1905). From a strategic point of view, it was not less important than any of these, much to the contrary, inasmuch as it assured the Portuguese, during almost a century, the freehold of the Indian ocean; it considerably lamed the power and prestige of the Turks, who were then the terror of Europe; it marks the beginning of a long period of domain of Asia by the Europeans, which only ended with the entrance of Japan in the Second World War.

Age of Discoveries Sometimes

in History, the light of Reason shines brighter: Ancient Greece, Renaissance,

the Space Race, the Internet.

Circa 1300: protecting

Knowledge; like Aristarco and Ptolomeu's "Round Earth", they

turned their back on Europe and created:

"Portugal is their cradle and the world their grave" Popular saying

Chronology of the Portuguese Voyages of Discovery

Bibliografy: Copyright © A.N.C.-

Associação

Nacional de Cruzeiros / Library Sá da Costa Editor / Cmdr. Saturnino

Monteiro / DancingWithDolphins® |

||||||||||

Print this page | Age of Discovery | World Map | Battle of Diu | Forefather of the Beaufort Table | Naval administration | Longitude | XVIcentury Ships

Home | Yongala | 3 Day trips | 1 Day trips | Book Me |